Travel nurses have held the upper hand for most of the pandemic, with providers willing to pay hundreds of dollars an hour for the temporary help needed to care for patients during the public health emergency.

But as COVID-19 cases declined, so too have those rates and the demand for temporary nurses. Nurses who once earned $10,000 a week are getting that much for a month’s work, said Kaycee Turner, a travel nurse recruiter with Loyal Source, a workforce solutions provider.

And many nurses, accustomed to higher wages, don’t want to take jobs that pay less. That’s where hospitals see an opportunity. To recruit nurses and to bolster their own staffing ranks amid long-term nursing shortages, some health systems are launching their own in-house staffing agencies. Nurses are paid a premium to rotate within their own systems, giving hospitals workforce flexibility, a talent pipeline and a lower cost structure than if they worked with an outside agency.

Some systems offer travel nurses higher wages than what’s available through an external agency, crimping those companies’ ability to attract talent.

“We have openings. They’re not willing to take them,” Turner said of travel nurses.

From February 2021 to February 2022, the median travel nurse rate rose 56% to $139 per hour, according to healthcare consultancy Kaufman Hall’s survey of 900 U.S. hospitals. In February 2020, the median rate was $59 per hour. Meanwhile, the median rate for a staff nurse rose only 11% to $40 per hour in February 2022 compared with February 2020.

Overall, median contract labor expenses went from representing 2% of hospitals’ labor expenses in February 2020 to 5% in February 2021 and 12% in February 2022, Kaufman Hall reported.

Labor costs can represent as much as 55% of a health system’s expenses, according to the firm.

“I think leading organizations are working to develop some very creative solutions,” said Therese Fitzpatrick, a senior vice president at Kaufman Hall who advises hospitals and health systems on staffing issues.

Some health systems are setting up pools of nurses who travel throughout the system’s network, while others are creating their own branded staffing companies, Fitzpatrick said.

Internal Solutions

UPMC, a not-for-profit health system based in Pittsburgh, in December launched UPMC Travel Staffing with plans to recruit 800 nurses and some surgical technicians. With a set rate of $85 per hour, with extra incentives for working nights and weekends, the system can hire two in-house travel nurses for the price of one from an outside agency.

“We’ve eliminated the middleman,” said Holly Lorenz, chief nurse executive at UPMC. “We are employer and vendor at the same time. We cut out the overhead.”

So far, of the workers recruited into UPMC’s program, 35% have been staff nurses who moved to the travel side and 65% have been external hires.

“As our internal travel staffing program grows, we absolutely plan to use less and less agency staff,” Lorenz said. “Each week, there are incrementally more people who are not external agency here.”

The hope was both to form a new pipeline of workers and to retain staff who otherwise might leave, Lorenz said. While the system previously considered starting its own staffing agency, it took the pandemic to make it clear how attractive some nurses find traveling and what a sustainable pay rate would be, Lorenz said.

“The mobility of nurses during the pandemic was really driven by where the money was,” Lorenz said. “We went in knowing this would be a long-term strategy for us.”

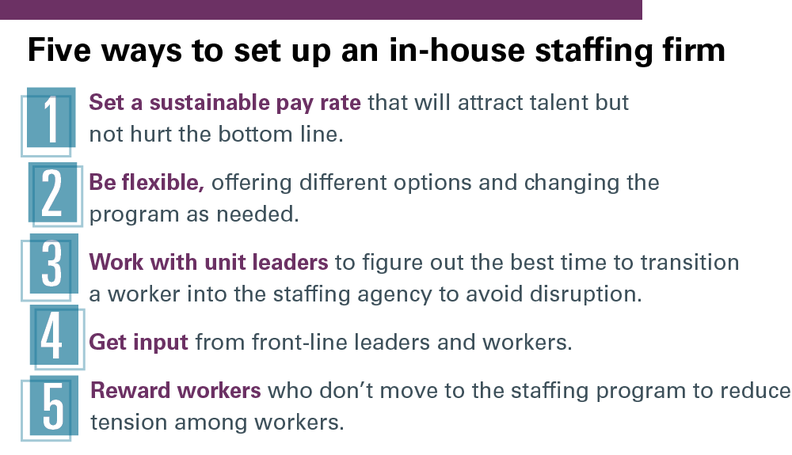

The system uses analytics to track where candidates come from, both internally and externally, and makes sure it doesn’t create shortages by recruiting too many staff nurses from its hospitals. Leaders also communicate regularly with managers to determine the best timing for a staff nurse to leave a particular department and move to the internal staffing agency so there isn’t tension, Lorenz said.

“We are not here to just take a chess board and move nurses around,” Lorenz said, noting that they’re targeting nurses who really want to make the switch. “It’s a lifestyle change.”

Lorenz said she has been pleasantly surprised by how many staff nurses decided to stay with UPMC through the new staffing program instead of going to an external agency and by those who have returned from an external agency.

Susan Myers left UPMC, where she had worked since 2013, early in the pandemic to become a travel nurse. She had been part of a local travel nursing program at UPMC, the precursor to what became its UPMC Travel Staffing, and wanted to give an external travel agency a try.

“They were obviously offering much higher salaries than what I was making on local contracts,” Myers said. “I wanted the flexibility of being able to travel at a distance if I wanted to and being more flexible in where I could go.”

For a year, she worked with four different agencies and traveled around Pennsylvania and Ohio. But when she saw UPMC’s ad for its new internal staffing agency in January, she signed up.

UPMC offered stable contracts, benefits, paid time off and a 401(k) plan with a matching component—all things she didn’t have through the other agency, she said. With an external agency, while she had freedom to choose where her next job would be, contracts weren’t always guaranteed and could be changed or canceled even after she accepted them.

“That was causing a lot of anxiety for me,” Myers said.

Under UPMC Travel Staffing, nurses are assigned six-week contracts at any site in the system’s footprint, which includes 40 hospitals in Pennsylvania and one each in New York and Maryland. UPMC pays a $2,880 travel allowance per assignment to anyone whose placement takes them more than 60 miles away from home.

UPMC also has revised how it compensates staff nurses, to reward them for staying with the system and not moving into its own travel program. For new nurses, that means a higher base salary that amounts to an additional $20,000 over the first four years, Lorenz said.

“It is probably the best thing we’ve ever done for our staff nurses,” she said.

Download Modern Healthcare’s app to stay informed when industry news breaks.

Learn From Your Staff

Systems considering launching an internal staffing agency should reach out to nurse leaders and front-line nurses for input, Lorenz said. And they should “think creatively and be prepared to be flexible and nimble” as they evaluate what is and what isn’t working, she said.

In September, WellSpan Health, which operates in south central Pennsylvania, launched a system-wide travel staffing program called WellStaffed, and it will remain a “core strategy,” said Bob Batory, senior vice president and chief human resources officer. About 55 registered nurses are in the pool, as well as about a dozen nursing assistants, he said.

Pandemic staffing agreements lead to long-term hospital collaboration

“We just think it’s a smart strategy, and we have plans to grow this beyond nursing,” Batory said.

He stressed the importance of involving front-line leaders throughout the process.

“Success hinges on the understanding of the needs of each unit and hospital across the system. Involving the front-line leaders in the process helps the program evolve,” Batory said.

Although it’s more expensive than using core staffing, the internal agency is less expensive than an outside agency, Batory added. Another upside of an in-house agency: Nurses spend less time in orientation and more time caring for patients because nurses only rotate within the WellSpan system, Batory said.

The program also allows WellSpan to better know the workers who are traveling between sites. They receive performance reviews, complete continuing education and advance through the system’s ranks.

“Sometimes you’re paying premium labor rates for individuals who are not the best at their profession,” Batory said.

Offering Flexibility

Ruth Brainerd, who has been a nurse for 20 years, worked at WellSpan’s York Hospital near her home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, before she joined WellStaffed a few months ago. At York Hospital, she moved between units, signing up for shifts as her schedule allowed.

“Pretty much all of my work experience had been at York Hospital. This gave me an opportunity to see how other facilities do things,” Brainerd said. “It’s like having a fresh start every few weeks. During the pandemic, that was really nice because there was a lot of burnout and frustration.”

Because she is a nursing instructor at a local college, she works on an as-needed basis and picks up shifts that fit her teaching schedule. She hadn’t considered travel nursing previously because she didn’t want to give up the benefits, retirement plan and seniority granted to her as an employee of a health system.

“To me, that outweighed maybe the interesting part of travel nursing,” Brainerd said.

But now she gets to move around within the system, instead of just at one hospital, without forgoing those perks, she said.

The internal staffing agency helps the system attract different kinds of workers who want something other than the standard full-time staff nursing job, Batory said.

“Having that kind of flexibility with multiple options provides multiple pipelines to staff the organization, he said.

Batory said the program’s professional growth opportunities have increased its popularity.

“Some nurses had intensive care and emergency department experience, yet there was not an established way for them to work in both environments prior to WellStaffed. Now they can work in various specialties and continue to challenge themselves professionally, while staying within our organization,” Batory said.

Henry Ford Health launched its internal staffing agency, BestChoice, five years ago. The system wanted to reduce the costs of external agency staffing, said Jan Harrington-Davis, vice president of talent acquisition and workforce diversity.

Its internal agency has grown during the pandemic. The system pays a BestChoice nurse $50 to $55 per hour compared with an hourly rate of $100 to $150 for external agency nurses, she said. Participants don’t qualify for benefits through the health system.

BestChoice is open to nurses, dialysis technicians, medical assistants and emergency department technicians. Most of the program’s participants have other roles, either at Henry Ford Health or other local healthcare providers, Harrington-Davis said. Sometimes Henry Ford recruits BestChoice nurses to join the system as permanent staff.

Henry Ford Health has 3,000 open positions, about 900 of which are for registered nurses, and has been using sign-on bonuses, an internal referral campaign and a human resources call center, in addition to the internal staffing agency, to help fill those spots.

“We are seeing where employees are coming back from agency assignments back into full-time and part-time roles,” Harrington-Davis said.

The program continues to evolve as the system works to contain costs while remaining competitive in the job market, she said.

“We’re still in a time that we’ve never been in before, and I think every single day we are learning,” Harrington-Davis said. “It’s definitely a space where we’re still learning and leaning on other organizations as well.”